It's been three years since a colleague approached me with the seemingly casual question: "Hey, we're initiating a new project and need someone who will lead it technically. Would you be interested?". "For sure!" I didn't have to think about it twice.

I like being involved in architectural decisions, trying to crack various programming nuts around, and have multiple objections on how things should be delivered, tested, or tracked. So it was natural for me to enlarge and strengthen my plate.

And then people happened.

Beginnings didn't show any adverse symptoms. We formed the team, delivered the first release, folks happy. However, later on, someone started mentioning how he isn't pleased about the product vision and that we have tasks defined just for next week at most. Another got into trouble with his coworker from a different team, and other similar human psyche mysteries unfold. And what became even more surprising - it was me who was supposed to act!

Indeed, there were many aspects of being a tech lead I hadn't anticipated. Eventually, it led me to step down and pursue a carrier as an individual contributor. Nonetheless, I learned hell a lot from this experience, and in the next lines, I would like to share my "discoveries".

Mountain summit is narrow and far from others.

A peculiar sense of loneliness crept first into the surface. As a developer, you never work alone but in a team with other developers, but once I got into the new role, there was only a single instance of tech lead - me. If you're considering a managerial position, be prepared for this. As you climb up, the path begins to disappear.

Sure, most colleagues around you will help you, but you must reach out farther than before to meet people at the same level. More often, even beyond your company. Building a stronger connection to people in the same role, although they might be sitting at a different location or even country, is something I undervalued initially, but I shouldn't.

Being direct, like for real, grants you safer landings.

Early in the morning of August 6, 1997, a Korean Air flight no. 801 crashed into a mountainside on Guam. Why did it happen? Pilots decided on the visual approach to the runway, despite the weather not being optimal. It was raining above the island. During the landing procedure, the captain mistakenly believed there're closer to the airport.

What's more, the first officer and flight engineer realized something is not right. But they didn't speak up clearly to the captain. Instead, they inclined to indirect suggestions and hints: "Don't you think it rains more?", "Not in sight?" or "Captain, the weather radar helped us a lot."

Both men were aware of imminent danger, yet the plane still crashed! They didn't want to question the captain's authority. Korean culture is traditionally hierarchical. Not by any coincidence, Korean Air recorded much more accidents than airlines from western countries by that time before they brought David Greenberg from the US to reform their operations.

Why am I saying this story here? (Which you can read about in the book Outliers btw.)

I made a similar mistake in some one-to-one meetings, for example, when I needed to motivate my colleague to change his attitude to one particular problem. In the end, a message never landed as it was too ambiguous, while I got upset that there's no visible improvement. I was trying to be too friendly as I liked having him in the team otherwise and didn't like the idea of him getting angry and leaving for a different team or even company.

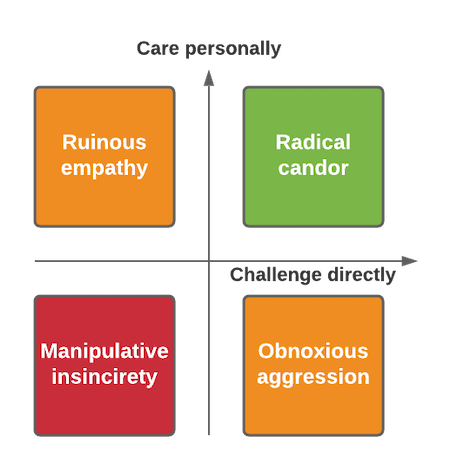

The fact is that this was purely a construct of my mind, which was counterproductive for all involved. Providing honest feedback is usually the best we can do. What I did was ruinous empathy. If in doubt, I highly recommend the book Radical Candor.

Sharing is caring.

As a developer, I always wanted to be involved in all hard to crack issues. And rarely said NO when such opportunity had come. Fortunately, the team and scrum master usually made sure I'm not busy working on multiple tasks simultaneously. Nonetheless, with stepping into the tech lead role, this barrier had fallen (we didn't have any scrum master or agile coach to stop me), and I had to learn the hard way context switching is not an option.

Before I fully acknowledged that truth, I put the whole team's work into danger. After initial successes, our velocity significantly dropped as I kept myself preoccupied with several challenging tasks that took forever to deliver for real. Meanwhile, colleagues weren't moving much with their business domain knowledge: I ate most exciting stuff for myself.

Some tech debt also quickly accumulated because I was too busy to do in-depth reviews of other application parts.

Lesson learned: share the workload and delegate, focus on finishing the work, not starting. And knowing when to say NO is an important skill.

By the way, that hardly gained experience helped me eventually in another aspect. I'm no longer behaving like a babysitter at the workshops towards juniors. Instead of solving ostensibly unrelated issues for them, I let them try by themselves first - or at least more often.

Don't shoot too fast.

Another point relates to the one above. Don't say out loud hasty conclusions too quickly. When it comes to gross estimation of future plans, product owners and stakeholders can shift their priorities if it seems it will take too long, even before grooming sessions. It's always good to remember team capacity and individual skills to avoid the trap of overconfidence.

Here are also some practical lessons I learned when I was part of some decision making. Because sometimes, things go awry even though not a single experienced participant saw any risks. If the new proposal looks too promising, try the following:

- Imagine the project or new approach fails, why it would happen?

- If there is an alternative, compare the proposal with that instead of old.

- If it still looks so great, ask yourself: Do I consider all sides, or I'm putting all weight on facts confirming my belief in the idea?

Retrospect in big.

I designed the article mainly as a retrospective of my tech lead intermezzo. Plenty of shortcomings I committed I saw before, and yet I did them too.

But I believe there were some good parts too. One thing that worked particularly well was organizing a Squad Health Check. As we're usually busy doing all the stuff, we sometimes forget to stop, take a breath and step aside for a while to check the overall picture. The health check proved to be the best mechanism to capture it.

Everything is well described in the Spotify blog post, so here are some additions:

- Turn disadvantages to advantages. For example, we were a remote team, but we scheduled it when we met at the same place and joined it with informal follow up at the restaurant, discovering local cuisine. And discussions got richer. Similarly, if it's still corona time, you can ship everyone, e.g., a bottle of wine, and enjoy some slack time on how you spend time under lock.

- Don't throw it into a drawer. It's great to talk things out, but it's much better when actual issues got addressed. Dedicate one retrospective or additional time between two health check sessions to briefly reiterate how you are standing.

Read & listen more:

- Squad Health Check model – visualizing what to improve

- GOTO 2020 • Talking With Tech Leads • Patrick Kua

- GOTO 2017 • How to Take Great Engineers & Make Them Great Technical Leaders • Courtney Hemphill

- 5 Practical Software Development Metrics Every Agile Leader Needs

- You're About to Make a Terrible Mistake

- Make It Stick